Using Subsidies to Repay Loans

In recent years, governments around the world have started using subsidies to help individuals and businesses pay back their loans. On paper, it looks like smart support — easing the pressure on borrowers, avoiding mass defaults, and keeping the credit system stable during tough times. But beneath the surface, the story gets more complicated. This isn’t just about giving people a boost. It’s about reshaping how we think about debt, risk, and responsibility — and that shift brings long-term consequences most people don’t see coming.

Why Subsidies Are Being Used to Cover Debt

Economic shocks — pandemics, inflation, droughts, energy crises — have pushed many borrowers to the edge. When businesses shut down or incomes shrink overnight, paying off loans becomes impossible. In those moments, governments step in. They launch support programs, freeze interest, or offer targeted subsidies to cover a portion of monthly repayments. It’s crisis response, designed to stop domino effects: defaults, credit crunches, and bankruptcies.

But as these interventions grow more common, the line between short-term help and long-term dependency starts to blur. What was once an emergency measure is slowly becoming part of normal debt management. And that raises serious questions about who’s responsible for a loan when a subsidy enters the equation — the borrower, the lender, or the state?

The Appeal: Relief Without Forgiveness

Subsidy-backed repayment programs strike a middle ground. They offer borrowers real financial breathing room without requiring full debt cancellation, which can be politically explosive. For governments, it’s a way to inject money into the system without setting a precedent that debts can simply vanish. For lenders, it lowers their risk — repayments continue, defaults fall, and portfolios stay healthier than they otherwise would.

For example, a government might offer to cover 30% of loan repayments for struggling farmers, startups, or low-income households. That assistance helps borrowers stay current on payments and maintain their credit history, which matters if they need financing in the future. In most cases, it’s framed as a temporary bridge, not a permanent crutch. But in practice, these bridges often keep getting extended.

How This Changes Borrower Behavior

When people know there’s a backup plan, they behave differently. Subsidy-driven repayment programs can make borrowers less cautious. If you believe the state will help cover your loan in hard times, you may take bigger financial risks or borrow more than you otherwise would. It’s not necessarily reckless — but it does soften the edge of personal accountability.

This behavior shift isn’t theoretical. In countries where subsidy-backed repayments have become common, lenders report an uptick in high-risk applications, particularly from people who wouldn’t have qualified before. Some borrowers now see loans as partially public money — and adjust their expectations accordingly. That erodes what economists call “market discipline” — the natural checks and balances that come from knowing you’re fully responsible for the debt you take on.

Are We Subsidizing Risk, or Rewarding Resilience?

There’s a fine line between helping those who need it and encouraging risky behavior. Some critics argue that widespread subsidy use creates a kind of moral hazard — protecting borrowers from the consequences of overborrowing or poor planning. Others say this view ignores the realities many people face: unpredictable incomes, rising costs, and financial systems that were never designed for average households in crisis.

What makes the difference is targeting. When subsidies are tied to specific shocks — like crop failure, health emergencies, or job loss — they can reward responsible borrowers trying to weather extraordinary events. But when support becomes too broad or too frequent, it risks normalizing borrowing without risk. And that can be dangerous for both individuals and lenders in the long run.

The Hidden Cost to Public Finance

Subsidizing loan repayments isn’t free. Governments fund these programs through taxes, debt, or reallocated budgets — all of which have limits. As subsidy-backed lending grows, so does the cost to the public purse. And that’s where the trade-off comes in. Every dollar used to repay private debt is a dollar not used elsewhere: education, infrastructure, healthcare, or investment in future growth.

There’s also a time factor. Short-term subsidies often come with long-term fiscal consequences. If the practice becomes a permanent fixture in public policy, countries may find themselves supporting a credit system that depends on state money to stay afloat. At that point, we’re not just helping borrowers — we’re underwriting the credit market itself.

What Happens When the Support Ends?

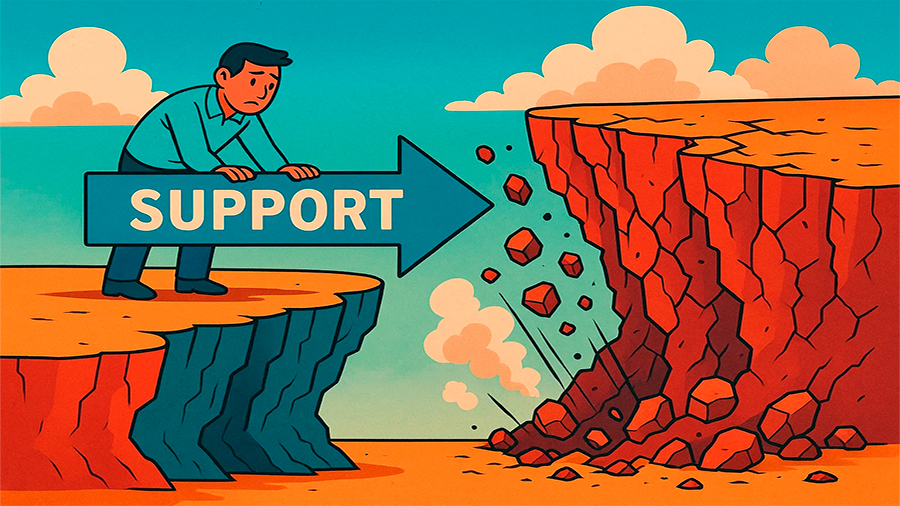

This is the hardest part. Temporary support eventually has to stop — but what happens then? If borrowers have relied on subsidies for too long, they may not be prepared for full repayments. Businesses that stayed open thanks to partial loan coverage might struggle when the full cost returns. And lenders, having grown used to low default rates thanks to government help, may be blindsided by a spike in non-performance.

This creates a cliff effect. Everything looks stable during the subsidy period — but once it ends, cracks appear fast. That’s why successful programs often include a clear exit strategy: gradual reduction of support, financial counseling, or options to restructure remaining debt. Without those tools, the end of subsidies can cause the very crisis they were meant to avoid.

Better Ways to Support Borrowers?

Subsidizing loan repayment isn’t the only option. Some experts suggest building more flexible loan products — ones that adjust automatically based on income or economic conditions. Others recommend broader use of loan guarantees, where the state backs the lender in case of default rather than funding direct payments. These alternatives still support borrowers but avoid the behavioral shift that full subsidies can trigger.

Education also plays a role. Helping people understand debt — how it works, what it costs, and how it fits into long-term planning — can reduce overborrowing in the first place. If we build systems that encourage responsibility without punishing hardship, subsidies become less of a necessity and more of a targeted tool.

The Conclusion

Using subsidies to repay loans changes more than monthly bills — it changes how we think about debt itself. It shifts responsibility, alters incentives, and stretches public budgets in ways that aren’t always obvious at first. For some, it’s a lifeline. For others, it’s a signal that risk no longer carries weight. The challenge is finding balance: supporting those in real need without encouraging a culture where debt feels consequence-free. Because when that line disappears, the cost isn’t just financial — it’s structural.